From climate science to economic fear: Prebunking the narratives aiming to delegitimize COP30

Analysis of 70,000 social media posts unearth the pressing narratives aimed at delegitimizing global climate goals

The debate over climate change action has shifted from the science to a conflict over economic cost and political legitimacy.

The world’s climate negotiators, heading deep into the Amazon in Belém, Brazil, for COP30, are facing key political challenges as disinformation campaigns are used to attack the legitimacy of the conference.

Promises are often made at the United Nations Climate Change Conferences. Known as COPs, these gatherings are where countries and other ‘parties’ that are signed up to the Framework Convention on Climate Change meet annually.

That list of parties is long. In a rare show of global unity, 198 parties have signed up to the 1992 treaty that pledges to “stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations” — although the treaty is not legally binding.

As the climate emergency has become more acute in recent years, the COP summits have drawn criticism, even from those who support their aims. This year’s COP is almost a fortnight long, not including a summit of world leaders beforehand, and many of its tens of thousands of attendees will have to fly to get there. Sometimes, as this year, the conferences are held in ecologically vulnerable areas, a deliberate choice that organizers say aims to raise awareness about the effects of climate change.

A group of leading climate policy experts, including Ban Ki-moon, Mary Robinson and Christiana Figueres, wrote in a joint letter last year that UN climate summits were “no longer fit for purpose”, adding that it was time to shift from negotiation to implementation. They also called for stricter rules on fossil fuel lobbying during the conference held in major oil and gas producer, Azerbaijan. A year earlier, the conference was held in Dubai, another oil-rich state.

Away from the logistics of the conference itself, public trust in what can truly be achieved at a policy level is shaky. Thirty years on from the first edition, the Earth is a worse situation. And just last month, 10 years after the Paris Climate Agreement was signed, UN Secretary-General António Guterres acknowledged that humanity had missed its target of limiting global heating to +1.5°C.

The mammoth task of repairing environmental damage everywhere requires cooperation in every corner of the globe. Despite this, the United States announced that it would not be sending any high-level officials to the conference, weeks after President Donald Trump stood up at the UN General Assembly and called climate change the world’s “greatest con job”.

Along with the legitimate criticism of the COP summits, there is a significant disinformation element that threatens to derail any progress that does spring from international cooperation. From climate change denial to economic obfuscation and spiralling climate fatalism, many strands of narratives have been woven around efforts to remedy our failing planet.

The method

An analysis by members of Eurovision News Spotlight of climate disinformation appearing on social media in Europe shows an increasingly sophisticated approach that has moved beyond simplistic climate denial.

The analysis focused on social media activity spanning five months, from May 1 to October 1, 2025. This period was strategically chosen to capture the evolution of narratives from post-COP29 political cycles through the major summer news events and into the final months before COP30 in Belém.

The analysis employed a quantitative content analysis of posts on the X platform (formerly Twitter) to map the discourse attacking global climate ambition in the lead-up to COP30.

A total of 70,000 tweets were collected: a sample of 10,000 each across Finland, Spain, Germany, Austria, the United Kingdom, Belgium and France, uncovering a multi-front playbook aimed at destabilizing the narrative around climate action.

The analysis suggests the presence of a campaign not to win a factual debate but to leverage psychological levers to create policy paralysis.

The psychology of climate misinformation

Climate denial campaigns go beyond challenging facts; they leverage how people process information and form beliefs. By leveraging our natural tendencies, these campaigns create doubt, foster discord, and can paralyse action. To effectively counter their impact, it’s crucial to understand four key psychological levers that they can manipulate.

Confirmation bias: People tend to seek out, interpret, and remember information that confirms their existing beliefs or political identity. Climate disinformation often tailors its message to specific political or ideological groups, making it instantly more palatable.

Motivated reasoning: This is the tendency to reject accurate information that conflicts with deeply held values or personal/economic interests. If a climate solution threatens a person’s job or lifestyle, they are motivated to find reasons to believe the disinformation that discredits that solution.

The propaganda technique: Disinformation campaigns often flood the zone with numerous, poorly supported, and easily debunked claims. The sheer volume makes it impossible for fact-checkers or the public to keep up, for example, creating the impression that “scientists are still debating.”

Availability heuristic: Emotional responses override rational thought. Disinformation often uses high-emotion language (anger, fear, outrage) to bypass critical thinking and encourage immediate sharing, especially on social media.

Index

Attacking solutions (Renewable energy and technology)

Economic denial

Attacking global governance & elite hypocrisy

Minimizing climate impacts

Discrediting messengers & institutions

1. Attacking solutions (Renewable energy and technology)

Renewable energy (like wind and solar) is unreliable, too expensive, and will cause massive blackouts.

Example: Following the April 28, 2025, blackout across Spain and Portugal, misinformation quickly spread, falsely blaming it on Spain’s growing reliance on solar and wind power.

Spain’s far-right party, Vox, accused the government of concealing the true cause. Parliamentary spokesperson Pepa Millán told Congress that officials “know perfectly well what has happened and they don’t want to say it,” directly blaming the government for the blackout.

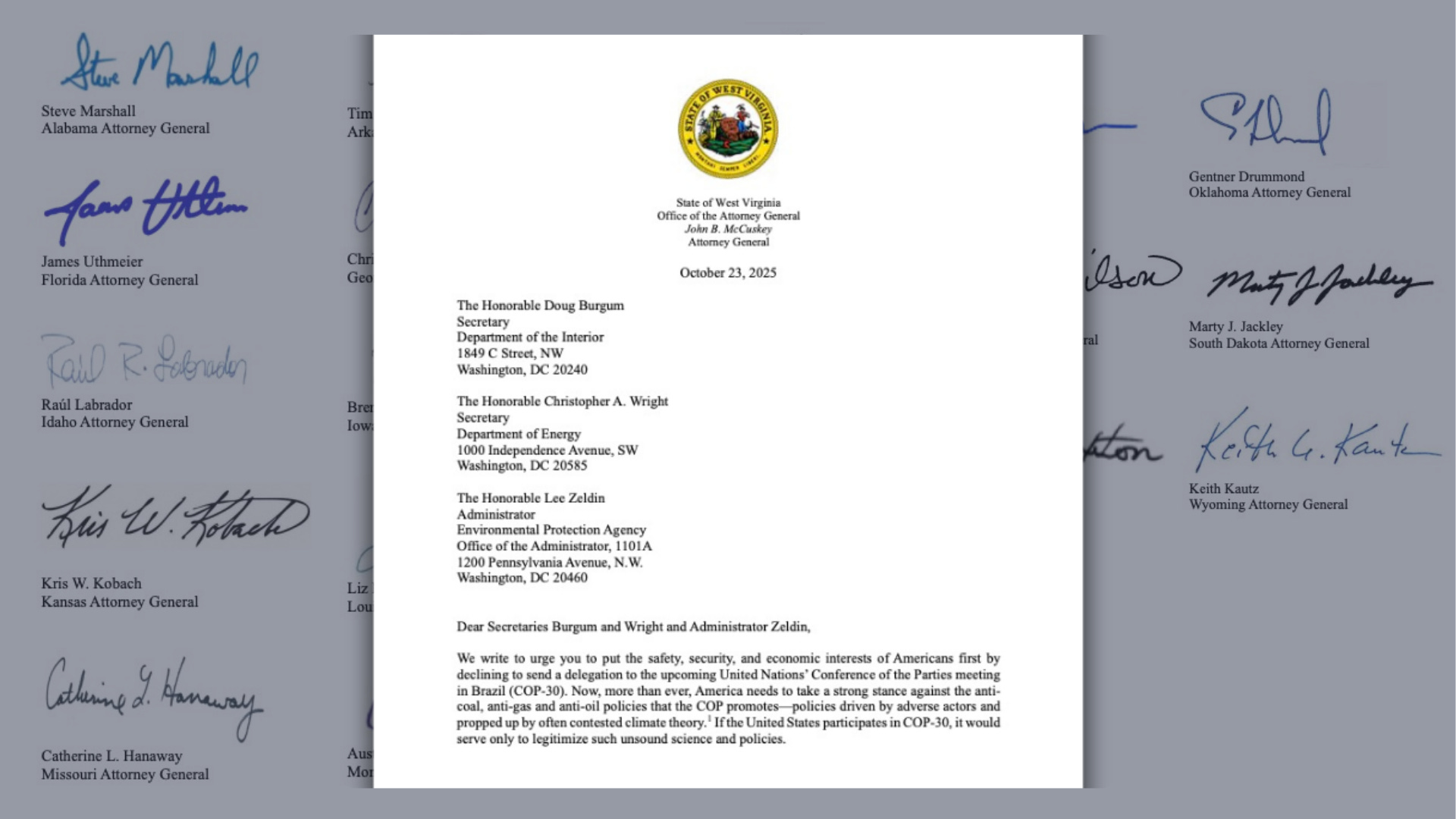

In the United States, 17 Republican Attorneys General cited the Spanish blackout in a public letter urging the US government to boycott COP30.

Despite the growing tide of misinformation, investigators from ENTSO-E, the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity, identified the real cause: voltage-control failures and cascading technical faults, not solar or wind power.

Why people believe it: FUD, fear, and cognitive bias

The belief that renewable energy is fundamentally unreliable is not grounded in engineering principles but rather in a successful rhetorical strategy. This narrative exploits the Availability Heuristic, a cognitive shortcut that leads people to think that emotionally charged events they can easily remember are more likely to occur than they really are.

Cass R. Sunstein, the Robert Walmsley University Professor at Harvard Law School, argues that our decision-making, both personal and political, is often driven by a psychological preference for a good story or a vivid image over statistics.

The FUD (Fear, Uncertainty, Doubt) campaign offers the public a simple reason to stick to the known energy infrastructure, while ignoring the external costs of fossil fuels—such as the massive health impacts from air pollution and the escalating disaster costs due to climate change—that are not reflected in their market price. The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) says that rapid growth in renewable energy use by 2030 could save up to USD 4.2 trillion per year worldwide.

Countering the narrative: Economic inevitability and engineering solutions

The foundation of the anti-renewable argument—that clean energy is too expensive—has been thoroughly undermined by market forces and technological progress.

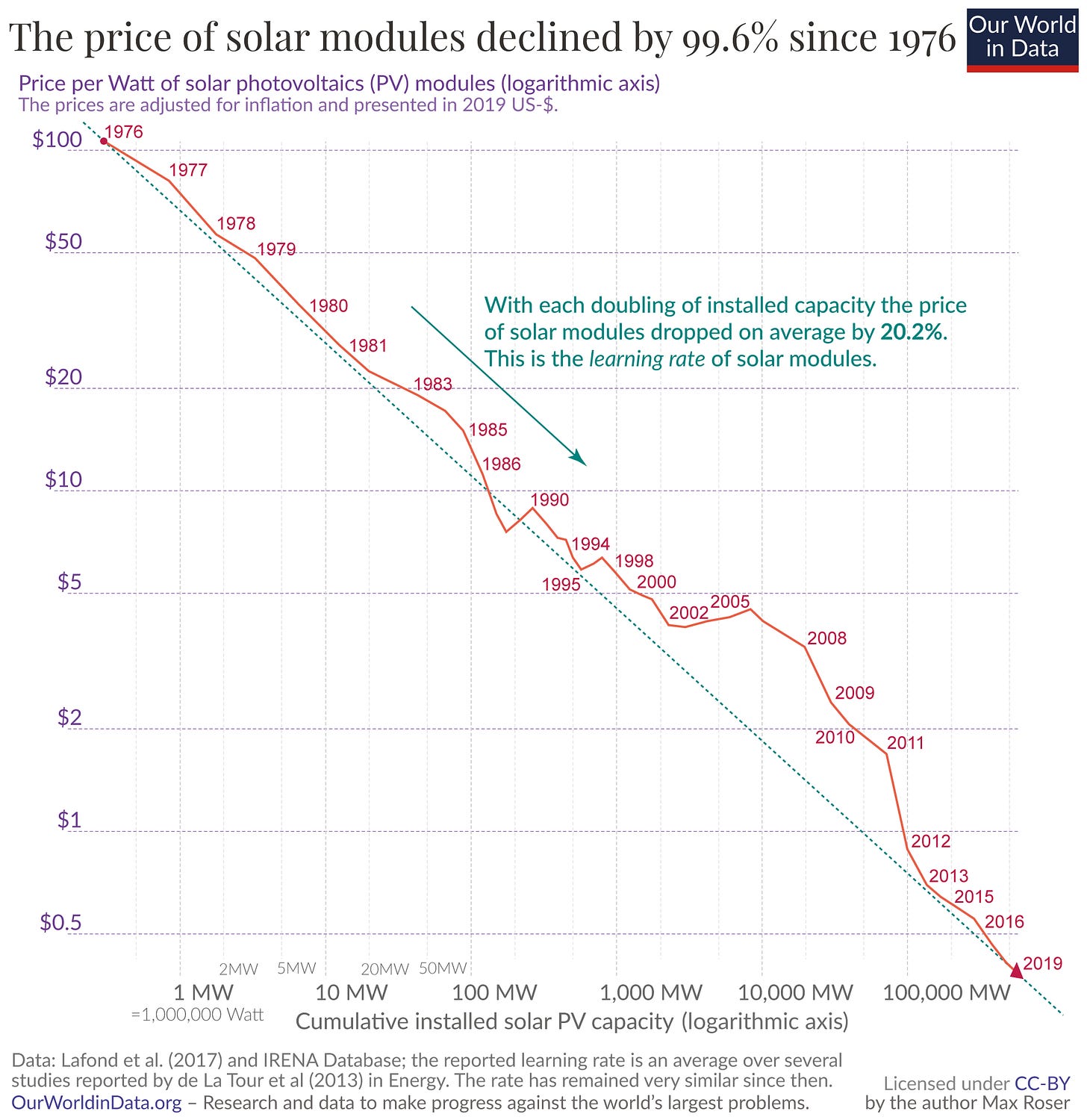

Solar photovoltaic costs have fallen by 90% in the last decade, onshore wind by 70%, and batteries by more than 90% according to a study by Global Change Data Lab, a non-profit organisation based in the United Kingdom, making new wind and solar projects the most economically competitive sources of electricity globally.

The decrease in cost comes as technologies follow Wright’s Law, or the experience curve effect, which states that technology becomes consistently cheaper as cumulative production increases.

The materials and land required for electric vehicles (EVs) and renewables are more environmentally destructive than burning fossil fuels.

Why people believe it: “Whataboutism” and false equivalence

This tactic attempts to discredit a solution by pointing out a different, albeit real, problem (e.g., mining for battery components), thereby creating a false equivalence that suggests no action is better than an imperfect one. Joakim Kulin, associate professor (Docent) in sociology at Sweden’s Umeå University, says this is recognized as a key discourse of climate delay used to justify inaction.

The shift to a green economy, which requires visible infrastructure like open-pit mines and wind/solar farms, is often viewed by the public as more damaging than the old system. Because the harm from fossil fuels, like invisible CO2 or distant oil pollution, is easier to ignore. The new visual impacts, being right in front of people, are therefore more likely to be perceived as a bigger, more immediate threat, according to a study by researchers at Slovakia’s Technical University of Košice.

A 2021 white paper by the International Council on Clean Transportation states that people often focus on the considerable initial environmental “cost” of manufacturing an EV battery or a solar panel. This initial impact is dramatic, but they fail to account for the years of operational benefits (zero emissions) that result from avoiding the continuous, cumulative damage of burning fossil fuels.

Countering the narrative: Fewer emissions from EVs, but critical minerals key

Running an electric vehicle is not completely free of fossil fuels, even though it’s possible to generate electricity entirely from renewables. For example, the EU says that in 2023, 45% of the power generated came from renewables, while fossil fuel power plants, such as gas and coal, accounted for 31.7% of electricity (the rest was nuclear-generated). The amount of electricity in the grid that’s fully renewables-generated varies from country to country, but on the other hand, it’s unlikely to be 100% fossil-fuel generated — whereas a petrol or diesel car, by its nature, is 100% run on fossil fuels.

The other side of the EV argument is the energy and waste associated with manufacturing the cars. Some studies have shown that making an EV can create more pollution than a traditional car, because of the energy required to make the battery. However, a full lifecycle assessment by Argonne National Laboratory (used in an explainer published by the EPA) showed that while the beginning and end of an EV's life are more emissions-intensive, the impact of these vehicles is lower over their entire life, as they have no exhaust emissions. Sustainable and circular-economy practices, including battery recycling, are rapidly improving, but there is room to improve how we manage the disposal and recycling of all our battery and electronic devices, including cars.

The land requirements for renewable energy is another argument. It’s true that some renewable sources, like solar and wind energy, require large areas for installation and could harm biodiversity in those areas. However, a 2024 analysis by the European Environmental Bureau found that Europe has sufficient land to expand solar and wind energy without compromizing nature or agricultural needs.

Wind turbines, solar panels, and any associated batteries or cabling are also, at their core, tech devices that require specific materials that must be mined. The International Energy Agency, in its reports on global critical minerals, has consistently referenced increased demand for critical minerals such as copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt, graphite, and rare earth elements — specifically for energy transition applications and other technological uses. The impact of our increased use of these products — both for renewable energy and for our everyday tech devices — will be a key challenge for climate decision-makers in the years to come.

2. Economic denial

The solution to climate change, net zero, is economically damaging and will bankrupt the nation and impoverish normal people.

Example: The 2023 UK policy rollbacks (e.g., delaying the ban on petrol and diesel cars from 2030 to 2035) were justified by then-Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, who argued that it’s wrong to “impose such significant costs on working people.” This statement directly validated the “cost-scepticism” narrative pushed by groups like the Tufton Street network.

The risk of a “backlash” against the wider mission—the very outcome sought by the economic deniers—justified the policy pause to find a “pragmatic, proportionate, and realistic approach,” Sunak said at the time.

Sunak defended his climate rollbacks and referenced the financial anxiety argument in a BBC interview at the time, saying he did not believe “ordinary families up and down the country” should have to “fork out” thousands of pounds to make the transition to greener vehicles.

Why people believe it: Financial anxiety meets justification

This narrative succeeds by weaponizing financial anxieties among the population, a fear fuelled by rising costs and insecurity. When a policy (like a climate tax or regulation) is framed as a threat to one’s wallet, it triggers an emotional response that makes people less rational.

This fear is then rationalized through motivated reasoning, a cognitive bias in which people interpret information to support a desired conclusion, in this case, their economic stability. In the Journal of Economics, French economists Roland Bénabou and Jean Tirole theorize that people hold certain beliefs partly because they assign value to them, reflecting an implicit trade-off between accuracy and desirability.

Countering the narrative: Immeasurable cost of climate change itself

This is a question of short-term versus long-term thinking, and has been the subject of much debate. Which is more expensive: measures to end climate change now, or the cost climate change might incur in the future?

For decision-makers, finding the balance between the nation's financial health today and a healthy, economically sound population in the future is a tightrope walk. The long-term nature of some generational debates around climate change does not always align with the short-term electoral cycles in most European countries and across the Global North.

The economic narrative ignores the long-term, devastating costs of climate inaction. There are significant infrastructural and societal costs associated with extreme weather events — including reconstruction work, insurance payouts, and, indeed, deaths.

In a Q&A with Group Chief Economist for insurance giant AXA, Gilles Moëc — published on the firm’s own website — he said: “Often, the economic cost of climate change is first insidious then dramatic”. Outside of the obvious human cost of disasters, the rising frequency of extreme weather events causes disruptions in global supply chains or demands huge capital for things like building upgrades to adapt to new temperatures, he added.

Any climate volatility for farmers also adds to food insecurity, and is already leading to displacement in places like Central America, where environmental factors are playing a greater role in the movement of people north into the United States. In 2022 alone, more than 32.6 million people were displaced worldwide by floods, windstorms, earthquakes or droughts, according to a European Parliament briefing document about ‘climate refugees’.

It is difficult to count the true cost of climate change. However, a 2024 report commissioned by the International Chamber of Commerce estimated that climate-related extreme weather events cost the global economy more than €2 trillion in the previous decade.

Furthermore, market data shows the green transition is an economic opportunity; for example, new utility-scale solar and wind are often cheaper than new fossil fuel capacity (LCOE), and adaptation policies are net job creators (ILO estimates millions of new “green jobs”).

As for the cost to individuals: governments can choose whether or not to financially incentivize green choices. In some countries, it has proven politically unpopular to push voters towards changing their heating systems or their cars, for the benefit of a future that might be too far away for governments to reap the political reward. It’s up to world leaders to decide what measures today could be considered good value when the maths are done on the present and future cost of climate change to the economy.

The domestic policy to achieve net zero is an “unaffordable” and “ideological” burden on the nation...

Example: The Tufton Street network (e.g., Global Warming Policy Foundation/Net Zero Watch) in Westminster drives the “economic denial” campaign. This network, which has been accused of receiving “dark money” from US foundations linked to major fossil fuel companies (like Donors Trust), pushes the narrative that net zero will bankrupt the nation. This pressure is credited with leading to the 2023 UK policy rollbacks.

Why people believe it: The confluence of cost, control, and identity

The argument that net zero is too expensive and driven by “ideology” works because of practical motivated reasoning, the psychological tendency to believe what is easiest or most convenient, as shown in the model of climate inaction.

A study by academics into class aspects of the green transition and the threat of right-wing populism in Poland argues that without reducing social inequalities, the nationalist right will find a pretext to “defend” the “common people” against “additional financial burdens resulting from costly or disruptive environmental policies.”

By labeling net zero as “ideological,” critics suggest that climate goals are only for the rich and that immediate costs, such as heating bills, matter more than future environmental benefits.

The movement also exploits feelings of national control.

An analysis of energy nationalism by universities in Finland, Spain and Poland finds that critics claim climate goals force nations to hand over control of key energy resources and domestic industry to international groups, directly threatening national sovereignty.

Prioritizing domestic fossil fuels is now framed as “protecting energy security” and “self-sufficiency,” which the CIDOB Policy Brief (Spain) and the Independent Review of Net Zero (UK) both note are treated as patriotic duties. Writing in Global Studies Quarterly, academics Duncan McLaren and Olaf Corry argue that this converts climate action into a cultural fight for freedom against overreaching government, making calls for delay sound like essential national defence.

Countering the narrative: The cost of delay

The actual cost of this political strategy is the delay itself, which impedes any ability to try and stay under or close to the +1.5°C warming limit. Delay might be cheaper now, but stands to become more expensive in years to come when more impacts of climate change are felt. These impacts would not be as extreme if countries limited warming now.

For example, a study published in the Nature journal relating to Ireland found that “delayed mitigation brings forward the need for a net-zero target by five years, risks carbon lock-in and stranded assets, increases reliance on carbon dioxide removal technologies and leads to higher long-term mitigation costs”.

The cost of transition will continue to be a sticking point for governments and their economists, as they try to balance the books today with what could be coming down the tracks tomorrow.

3. Attacking global governance & elite hypocrisy

COP30 is hypocritical, just a lavish waste of time and money for global elites that won’t result in any real action.

The critique of major climate summits, such as the COPs, centres on hypocrisy. With thousands of delegates, most arriving by air, some using high-emission private jets, the event’s carbon footprint directly contradicts its core mission: reducing global emissions.

This makes the conference an easy target for critics to accuse the attendees of being out of touch. Those from political and corporate life who participate are often perceived as being insulated from the real-world costs of the energy transition—such as increased energy bills or job losses in fossil fuel sectors—and are seen as merely “virtue-signalling” while indulging in high-carbon lifestyles.

Why people believe it: The authenticity gap

These massive gatherings are frequently dismissed as wasteful. They are widely perceived not as serious working sessions, but rather as expensive “global cocktail parties” where substantive, actionable progress is minimal.

This scepticism is compounded by the historical reality of the international climate process, which has a long track record of agreements, like the Kyoto Protocol, failing to make a substantial impact on the climate problem. This pattern of historical failure actively erodes public confidence in the entire mechanism.

These perceived flaws fuel a powerful, ready-made narrative that is highly effective for anti-climate-action movements. This narrative simplifies the complex negotiations into a potent us-versus-them argument: “They are trying to destroy your economy and way of life with expensive, unreliable energy, while they party.”

This view thrives on the event’s bad optics, where readily available media images — delegates flying private, staying in luxury, and using motorcades — overshadow the slow, intricate, and less visually engaging work of the actual negotiations.

International climate conferences like COP30 are structurally vulnerable because they require extensive, high-carbon logistics — a new Amazon highway and cruise ships for delegates. Scholars note these visible, tangible contradictions create a legitimate “authenticity gap.” Anti-climate action narratives weaponize this hypocrisy, transforming these logistical flaws into intentional symbols of elite corruption.

They magnify the images of elite consumption and logistical flaws, framing them not as logistical errors, but as intentional symbols of corruption and disdain for the “ordinary person.” This exploitation leverages the Affect Heuristic, using high-emotion, outrage-inducing language (”fraudulent,” “rigged”) to bypass critical thought.

Example: The logistics for COP30 in Belém, Brazil, were strategically leveraged. This includes:

The construction of the Avenida Liberdade highway through 72 hectares of protected Amazon rainforest.

The decision was made to rent two cruise ships for 6,000 beds for delegate accommodation. Disinformation actors used these real logistical flaws to create a narrative of “unassailable hypocrisy.”

Countering the narrative: The role of COPs

COPs have long faced accusations of being lavish, and are fairly open to scrutiny as an event attended by governments, royalty and other so-called ‘elites’.

It’s fair to scrutinize the carbon and environmental impact of a conference that seeks to reduce all of the above. Organizers issued a note after critical news coverage, saying the road was not specifically built for the climate summit. However, local people still linked the road and the conference, telling reporters that while the project was talked about for 20 years, the approaching COP seemed to provide the justification to finally go ahead with it.

Another strand to this narrative says that nothing useful happens at COP summits. However, they represent the only mechanism for 198 parties to negotiate and formalize global climate agreements (like the Paris Agreement). Deals like these form the cornerstone of the world’s response to climate change, and the near-universal representation at COP is a rare unifying factor for the world.

The conferences are long and progress can be slow. This is due to the complexity of the event and the logistical, political, or even economic challenges. Countries and other parties at COP will be sent into negotiations to get the best deal for their region, argue for their domestic industries, and seek concessions on strict carbon targets.

COP30 is particularly important. At the 30th edition and 10 years after the signing of the Paris Climate Agreement, signatories are hearing that the targets set out in that plan will be missed. At this COP, they will be under pressure to come up with a solution that works for all.

The host nation, Brazil, is fundamentally hypocritical and corrupt; its internal policy contradictions prove its role as a global climate leader is a sham and that global action will fail.

Example: This narrative exploits two major contradictions simultaneously:

President Lula da Silva’s government is pursuing offshore oil development while hosting COP30.

The destruction of the Amazon rainforest for the Avenida Liberdade highway.

These actions are used to argue that Brazil’s rhetoric contradicts its actions.

Why people believe it: Financial gain hypocrisy

The strength of this narrative lies in its ability to appeal to two opposed audiences.

For climate sceptics and naysayers, Brazil’s perceived hypocrisy provides ammunition to delegitimize the entire concept of global climate action; the reasoning is that if a crucial global player cannot commit, the whole process is fundamentally flawed or merely a developed-world distraction.

For critics and the sceptical public, the narrative validates a deep-seated suspicion that political leaders everywhere prioritize tangible, short-term economic gains—like oil revenue or immediate infrastructure—over long-term environmental commitments.

The perceived betrayal of trust by a major player like Brazil fosters cynicism, leading to the belief that the pursuit of financial gain always prevails and making effective international action seem unattainable.

Countering the narrative: Brazil must work to re-establish credibility

Brazil has long been accused of climate hypocrisy. When President Lula returned to power in 2023, he pledged to make Brazil a climate action champion once more.

On the positive side, deforestation in the Amazon rainforest hit an 11-year low in 2025. However, the country has begun to loosen some environmental law and allowed oil drilling near the mouth of the Amazon River for the first time. Lula said the decision to drill for oil will raise revenue that would help fund the transition to cleaner energy. The debacle is a black stain on Brazil’s image, and unfolded just weeks before the COP30 summit.

The Brazilian government has defended its record. Environment minister Marina Silva said drilling for oil alongside climate ambitions is a contradiction that exists throughout the world. Lula himself has argued that the world will still need oil in the years to come, appearing to suggest that it and the pursuit of greener alternatives were not mutually exclusive.

On Avenida Liberdade, Brazilian federal officials explicitly distanced the federal administration’s planning for the COP conference and the highway project.

For those in power in Brazil, re-establishing the country as a hub of climate ambition will be a key challenge at COP30 and in the years to come. Contradictory policies or apparent hypocrisy risks undermining the country’s credibility as a leader in this space — a worry for a world looking to the custodians of the Amazon to save one of the world’s most important carbon sinks.

Developing nations, like Brazil, shouldn’t have to cut emissions because Western nations are the historical polluters. Therefore, the outcome is unfair.

Example: China has been operating coal-fired power plants for decades, accounting for a large share of the world’s current emissions. Forcing them to transition to renewables now puts an unfair economic burden on their development, while the West got rich polluting freely.

Why people believe it: Western nations are overwhelmingly responsible for the current climate crisis

The argument that developing nations should not bear equal responsibility for emission cuts is rooted in the principle of climate equity and historical responsibility.

A New York Times analysis found that 23 rich, industrialized countries are responsible for 50% of all historical emissions, while more than 150 countries are responsible for the rest.

This imbalance forms the ethical basis for “climate debt,” where the Global North is seen as owing the Global South for past pollution and its present-day impacts.

This is legally formalized in international agreements under the principle of “Common But Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities” (CBDR-RC). While all countries must take action on climate change, those that have polluted the most historically (the rich nations) have a greater responsibility.

Countering the narrative: Negotiations allow for individual arrangements

The principle of CBDR is already central to the UNFCCC. Developed nations do have a clear legal and moral obligation to provide climate finance and technology transfer. Some of the key points include that resources should be made available to improve the environment, taking into account the circumstances of developing countries, and that the special situation and needs of developing countries — particularly the most environmentally vulnerable — should be given special priority.

Over the years, there have also more specific concessions relating to the emissions outputs of a particular country, for example regarding the ozone layer, which allowed developing nations to delay compliance with overarching agreements. As the climate change situation — and our understanding of the science — evolves, negotiations at COP level allow for new arrangements to be put in place. Talks around how best to tackle the problem of climate change, in a way that is achievable for all countries, is a core part of what the COP summits are all about.

National sovereignty must be prioritized above global and legal climate obligations...

Example: Following the landmark ECtHR ruling in the KlimaSeniorinnen case, which found that Switzerland violated human rights due to insufficient climate action, the Swiss Parliament adopted an unprecedented declaration opposing the judgment. The country’s reliance on Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs) (buying carbon offsets abroad) is also used to portray Switzerland as attempting to “buy its way out.”

Why people believe it: Climate action as a zero-sum conflict

This narrative is problematic because it frames international climate action as a zero-sum conflict in which global obligations threaten local autonomy or sovereignty, according to J.B. Ruhl, Co-Director of the Energy, Environment and Land Use Program at Vanderbilt University.

It appeals directly to national pride and populist scepticism by positioning powerful, unelected international courts as antagonistic to the will of the domestic legislature. This is a potent political tool, as it transforms a legal critique into a defence of sovereignty, which resonates deeply with nationalist and conservative audiences worldwide.

The complexity of the solution — relying on financial mechanisms like ITMOs (carbon offsets) — is immediately weaponized as a “transparency trap.” The concept is difficult for the public to grasp, making it easy to portray as a secretive, elite attempt by the government (or corporations) to “buy their way out” of their true responsibility, avoiding genuine domestic change. The Swiss Parliament's legal defiance then becomes apparent ‘proof’ of the plot.

Sabina Schnell, international public administration researcher at Syracuse University, argues that a lack of transparency in a post-fact world reduces trust in government and increases polarisation in deliberation. Schnell suggests that by adopting a reasoned transparency model—explaining the ‘why’ behind decisions and information, based on logic rather than just raw data—transparency’s value could be restored.

Countering the narrative: International legal obligation and accountability

The ECtHR ruling is legally binding under international human rights law. If a state breaches such rules, a case can be brought domestically and as far as the European Court of Human Rights, where the state could be ordered to change course, pay compensation, or correct the breach. The argument to ‘prioritize’ national sovereignty is irrelevant, because breaching international law is illegal.

Meanwhile, ‘ITMOs’ are Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes — aka carbon credits which are earned for emissions reductions — and the Paris Climate Agreement allows countries to buy and sell these credits. Many countries rely on ITMOs to meet or come closer to meeting their emissions targets, but this means that countries could meet their targets without doing all the work themselves. As the trading of ITMOs becomes more popular and a market builds around them, countries will have to determine whether or not the system is working.

4. Minimizing climate impacts

The +1.5°C goal is already unattainable, so why bother? We should focus on adaptation, not mitigation.

Why people believe it: “Doomism” and Fatalism:

This idea gives people a psychological break from constant worry about climate change. Saying the +1.5 °C goal is impossible means people feel less responsible for making hard choices to stop climate change. It speaks to a sense of fatalism and overload with bad news, essentially permitting everyone to stop struggling with an impossible task. Experts call this “doomism,” which can lead to inaction.

Switching the focus to adaptation is an attractive and politically easy choice. It lets leaders and the public focus on visible, local, and immediate defences rather than tackling the global changes needed (such as phasing out fossil fuels). This approach makes avoiding action look like simple, realistic problem-solving.

Countering the narrative: The Importance of Every Tenth of a Degree

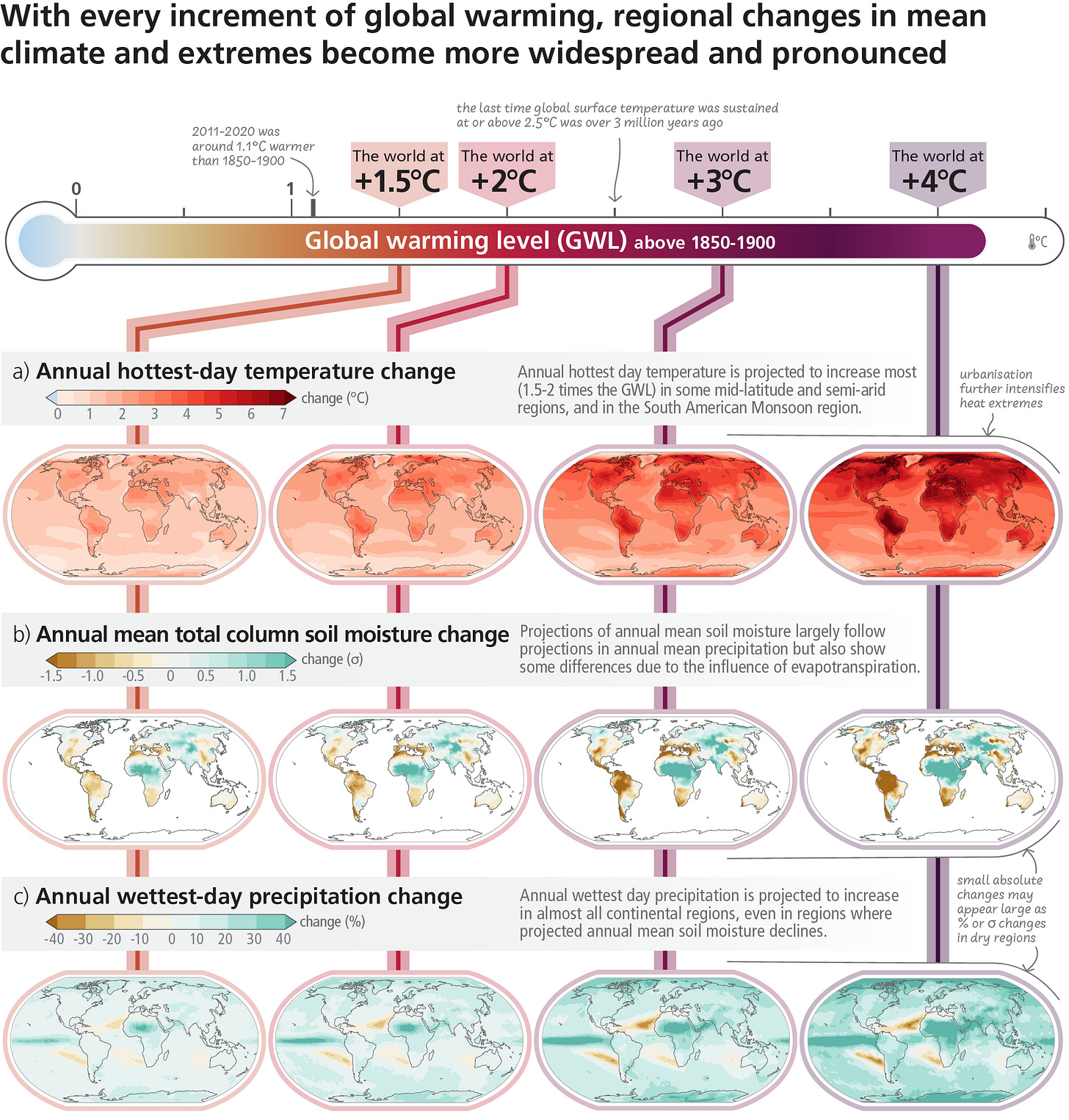

The +1.5°C target is not a cliff-edge. Even if the +1.5°C target is not reached, every fraction of a degree above it could bring vastly different consequences, as laid out in the most recent IPCC Assessment Report (AR6) about future risks. This explains why even if we miss the target (which is inevitable at this point, as acknowledged by the UN last month) it is still worth trying to limit global warming as much as possible.

The summary of the report goes on to explain: “Global warming will continue to increase in the near term (2021-2040) mainly due to increased cumulative CO2 emissions in nearly all considered scenarios and modelled pathways … Every increment of global warming will intensify multiple and concurrent hazards (high confidence). Deep, rapid, and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions would lead to a discernible slowdown in global warming within around two decades, and also to discernible changes in atmospheric composition within a few years (high confidence).”

In simple terms: Every increment of warming of the Earth’s surface, even from +1.5 to +1.6°C, significantly increases the risk and severity of impacts. Cutting emissions is still crucial to limit future harm, and even if it should have been dealt with years ago, the next best option is to start right now.

Climate change is real, but a slow, gradual process. There’s no need for immediate, costly, disruptive action now.

Why people believe it: Economic and cognitive biases

This narrative works because it taps into strong psychological and financial habits. It gives people a comfortable way out of taking immediate, expensive action. It makes climate solutions seem like a huge cost that can simply be put off. A paper by Debika Shome and Sabine Marx of Center for Research on Environmental Decisions at Columbia University says this urge to delay comes from present bias: we care more about immediate costs than future benefits, even if ignoring the future creates huge dangers.

Daniel Kahneman, a senior scholar at Princeton University, argues that calling for “pragmatism” or “small changes” appeals to people who see themselves as balanced, non-extreme centrists, letting them dismiss fast, significant changes as “radical” or “crazy.” It also takes advantage of how hard it is for the human brain to grasp fast growth and long-term risk.

Climate problems often build slowly until they suddenly hit a crisis point, making the idea of “slow and steady” feel correct. This slow-burn idea protects old business models and lets people think of delay as a sensible, sound financial choice, rather than the dangerous risk it actually is.

Countering the narrative: Rapid action can stem catastrophic tipping points

Climate science clearly shows that the changes are non-linear. We risk crossing tipping points, like Amazon dieback or ice sheet collapse, which could lead to unstoppable, catastrophic warming.

These tipping points are critical thresholds on our planet. When they are crossed, they can trigger abrupt and potentially irreversible changes. The Global Tipping Points Report for 2025 says that we’ve already reached one of these thresholds: the world’s coral reefs are irreversibly dying off. Parts of the polar ice sheets may also already be at this point, which would bring the world into a new era of unstoppable sea level rise. As for the Amazon, if it were to transform from a rainforest that absorbs a lot of carbon dioxide into a savannah that actually produces carbon, it would vastly accelerate warming and limit nature’s ability to cope with the greenhouse gases humanity is producing.

Action must be rapid and transformative to avoid these thresholds, as outlined by the IPCC.

5. Discrediting messengers & institutions

Climate advocates and leaders are personal hypocrites; therefore, their demands for climate action are ‘double standards’ and unreasonable to impose on the public.

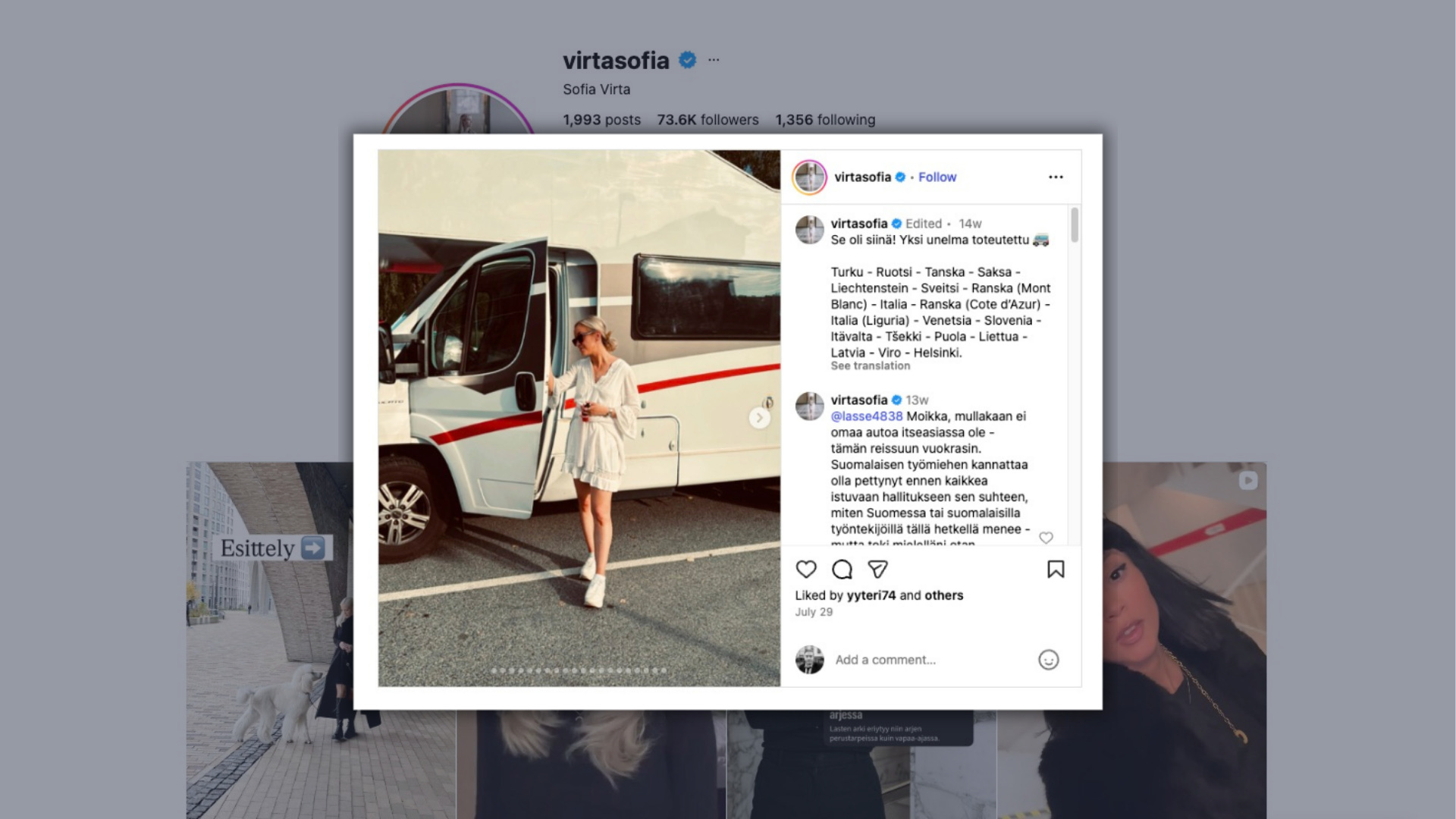

Example: The Finnish Green Party chair, Sofia Virta, was heavily targeted after posting about her vacation van trip through Europe. Right-wing representatives and social media users seized on the private drive, calling it a “double standard.”

Prominent representatives of the Finns Party and the National Coalition Party shared posts criticizing the Green Party for hypocrisy. Other X users argued that it is inappropriate to criticize others for private driving or eating meat if Virta drives around Europe for fun.’

Why people believe it: From policy effectiveness to personal moral integrity

This narrative shifts the discussion away from how well policies work and onto the leader’s personal morals. This lets people reject challenging, expensive demands for significant change (like emission cuts) by attacking the messenger’s perceived flawed personal life instead.

This approach is strongly driven by confirmation bias and the desire for an easy excuse. People who already doubt climate action or dislike ‘Green’ politics see a leader’s ‘private double standard’ (like the van trip) as a moral win. It confirms their belief that climate leaders are just elite hypocrites making rules they themselves ignore. This gives them an emotional reason to do nothing, as the moral blame is successfully moved away from systemic emissions and onto the perceived moral failure of elected officials.

Countering the narrative: Science doesn’t change regardless of messenger’s purity

Climate action is based on scientific consensus and systemic necessity, not the personal purity of individual advocates. There are many changes people might make if availability, time or financial restraints were not in the picture — for example, doing a food shop without purchasing any single-use plastic packaging would be very difficult in many countries, and there are people who live in remote areas for whom public transport is unavailable.

More broadly, a politician’s private travel choices, while open to scrutiny, do not invalidate the scientific data on which the policy platform for systemic emission reduction is built. Despite that, the personal behavior of politicians or activists on a green platform is highly scrutinized, so they sometimes self-police, make pledges or statements with their personal choices (Greta Thunberg famously sailed across the Atlantic in 2019 to attend a UN Climate summit in New York).

Conspiratorial Fusion

Climate policy (like net zero) is a covert instrument of social and economic manipulation and a component of a totalitarian plot...

Example: This narrative merges with suspicions and fears developed during past crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine war. Posts argue that the “fear-mongering propaganda” from those events is being “rewritten” to fit the climate crisis. The simple, core message is that all crises are “engineered falsehoods.”

Why people believe it: All crises are fabricated

The main reason people believe this story is that it gives a straightforward explanation for their deep mistrust of institutions.

Dutch social psychologist and author Sander van der Linden argues for those who already think influential people are corrupt, mixing events—like COVID-19 lockdowns, shortages, and climate policy (net zero)—makes all global crises seem like proof that they are constantly being lied to.

Professors at the Universities of Chicago and Ohio argue that this larger story changes how people see climate action. It is no longer just science; it is the newest step in a plot to take away freedoms and control economies. The intense feeling and simplicity of having a single enemy make this claim a powerful way to gather anti-establishment and far-right groups, giving them justification for their isolation and anger.

Countering the narrative: Proposed measures backed up by science

Climate policy is driven by overwhelming, peer-reviewed climate science and there is no evidence of a secret control plot. In fact, it would arguably be easier for domestic politicians to avoid climate measures, which can often be unpopular; they are pressured to do so by the weight of scientific evidence and legally-binding agreements (such as EU climate law which penalizes member states for non-compliance).

Mitigation and adaptation policies are openly implemented by governments, often in response to scientific bodies such as the IPCC and international agreements, like those negotiated and agreed upon at COP summits.

Measures like the green transition are publicly aimed at preventing catastrophic warming. As attitudes and the world economy shift in this direction, these measures are increasingly being presented as economic opportunities.

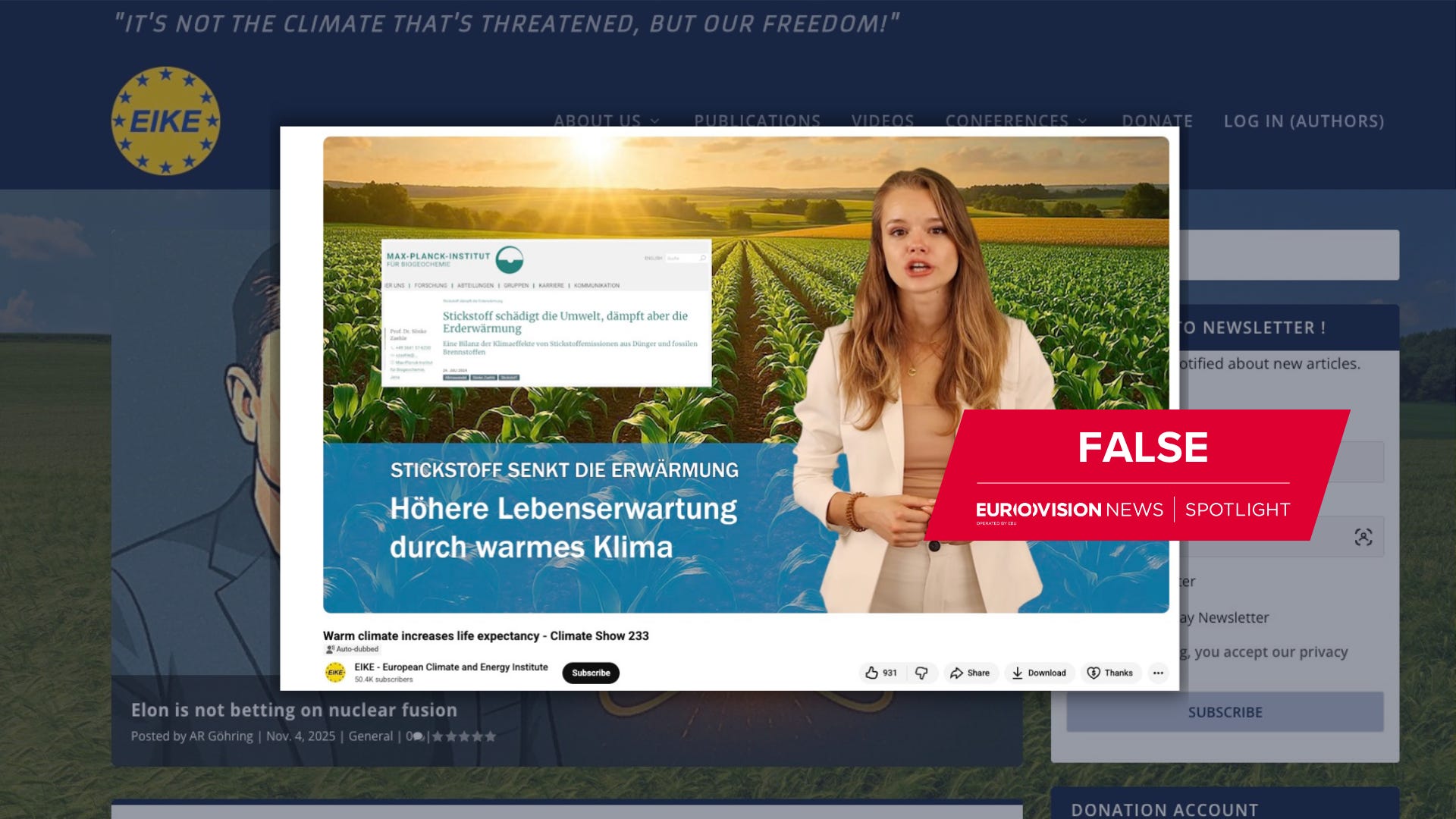

Expert faking

Expert façade are used to assert unjustified authority over discredited, unscientific claims, thereby exploiting the public’s natural esteem for academic credentials.

Example: The European Institute for Climate and Energy (EIKE) presents itself as a respected scientific institution in Austria to spread scientifically discredited claims.

EIKE has built a loyal audience, and its articles are widely shared within that community. One recent post, shared by user “A_nicht_nichtA,” falsely claimed that Antarctic and Arctic sea ice are expanding rather than melting.

In Germany, prominent climate-denier, economist Stefan Homburg lists himself as a professor at the University of Hannover. While he once held that position, he retired early after drifting toward conspiracy theories. Homburg actively replies to posts on X, especially those requesting Grok’s information. In addition, he uses hashtags such as #chemtrails and #klima frequently in his posts.

Why people believe it: Institutional camouflage and reputational legitimacy

This narrative operates through a sophisticated act of institutional camouflage. It exploits the public’s entirely reasonable deference to academic credentials and their general inability to vet obscure scientific bodies.

The creation of an “Expert Front” like EIKE or the strategic use of an academic title (e.g., Stefan Homburg’s retired professorship) instantly lends legitimacy to unscientific claims.

For the audience, the effortless appearance of authority, a clean website, and a professor’s name is sufficient proof that the information is trustworthy.

This is compounded by the fact that the actual, nuanced science is often difficult to access. This tactic provides a comforting, simple-to-believe “official” counter-narrative, mobilizing a loyal audience that values the perceived intellectual weight of these manufactured institutions over the consensus of established science.

Countering the narrative: Fact-check credentials

When anyone is speaking from a supposed place of authority, it’s essential to check their status and affiliations as much as possible. This should inform how much weight to give their statements. The situation for verifying a person on social media has become more difficult since verification badges became a paid-for item, but institutions may also indicate affiliated experts on their official pages.

For institutions in the age of misinformation, it has become more important to clearly distance themselves from people who are seen to be misusing past titles or completely falsifying any affiliation.

Meanwhile, EIKE is known for spreading unscientific denial claims. With a professional-looking name and website, a newcomer may not recognize that EIKE is not a legitimate scientific body. However, there is media reporting going back years and publicly-available information about it and other similar outfits, so viewers should aim to double-check any credentials, particularly when the topic is scientific or related to a specialism.

Conclusion

From weaponizing legitimate concerns over logistics in Belém to exploiting energy anxiety with false blackout narratives, there is no shortage of localized, fear-based content that delays systemic change until it is ecologically and economically too late.

By anticipating the next line of attack—whether it’s the cost of net zero, the ‘hypocrisy’ of climate leaders, or the perceived threat to national sovereignty—the international community can build public resilience, secure the mandate for the Just Transition and climate finance at COP30, and ensure that the vital work of staying below the +1.5°C threshold is not derailed by strategic, funded falsehoods.

The future of climate policy hinges not just on scientific consensus, but on our collective ability to safeguard the integrity of the conversation.

Eurovision News Spotlight will be monitoring the disinformation landscape during COP30.

Further reading as part of this investigation

References

A Case of Confirmation Bias. (2021). Journal of Economic Issues. [online] doi:https://doi.org/10.1080//00213624.2021.1940040.

Bayes, R. and Druckman, J.N. (2021). Motivated reasoning and climate change. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, [online] 42, pp.27–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.02.009.

Dimitrov, D., Ali, B.B., Shaar, S., Alam, F., Silvestri, F., Firooz, H., Nakov, P. and Da, G. (2021). Detecting Propaganda Techniques in Memes. [online] arXiv.org. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.08013 [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Kiran, G. (2022). Examining the Role of Availability Heuristic in Climate Crisis Belief. Berkeley Scientific Journal, [online] 26(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.5070/bs326157115.

Averre, D. and Reynolds, J. (2025). Could renewable energy be to blame for huge Spain blackout? How outage struck days after country’s grid ran entirely on green power for the first time. [online] Mail Online. Available at: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-14655733/How-huge-Spain-blackout-struck-days-grid-ran-entirely-green-power-time.html [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Wv.gov. (2025). Attorneys General: America should not attend UN Climate Change Conference. [online] Available at: https://ago.wv.gov/article/attorneys-general-america-should-not-attend-un-climate-change-conference [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Bloom, A. (n.d.). Introduction to Global Climate Change Available at: https://psfaculty.plantsciences.ucdavis.edu/courses/sas025/Chapter1.pdf [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Our World in Data. (2023). Solar panel prices have fallen by around 20% every time global capacity doubled. [online] Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/data-insights/solar-panel-prices-have-fallen-by-around-20-every-time-global-capacity-doubled [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Climate whataboutism and rightwing populism: how emissions blame-shifting translates nationalist attitudes into climate policy opposition. (2025). Environmental Politics. [online] doi:https://doi.org/10.1080//09644016.2024.2431393.

Edwards, M.R. and Trancik, J.E. (2022). Consequences of equivalency metric design for energy transitions and climate change. Climatic Change, [online] 175(1-2). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-022-03442-8.

Prime (2023). PM speech on Net Zero: 20 September 2023. [online] GOV.UK. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-speech-on-net-zero-20-september-2023 [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Johnson, B.B. (2011). Climate Change Communication: A Provocative Inquiry into Motives, Meanings, and Means. Risk Analysis, [online] 32(6), pp.973–991. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01731.x.

Towards decent work in a sustainable, low-carbon world. (n.d.). Available at: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_098504.pdf.

Tan, S., Minifie, J., Jones, E.R., Daniel, C. and Bharadwaj, A. (2025). Economic Growth Opportunities in a Greening World. [online] BCG Global. Available at: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2025/economic-growth-opportunities-greening-world [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Fenwick, J. (2022). 55 Tufton Street: The other black door shaping British politics. [online] Bbc.com. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-63039558 [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Bright, S. (2022). Opinion | Meet the Shadowy Groups Behind Britain’s Liz Truss. [online] Nytimes.com. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/06/opinion/truss-kwarteng-uk.html [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Limitation of Freedom of Expression on the grounds of national security/territorial integrity Weaponization of information and attacks on ‘information sovereignty’ -would freedom of expression standards suffice to tame the ‘information wars’?. (2020). Available at: https://pcmlp.socleg.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Weaponization-of-Info-v-FoE-14052020.pdf [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Odistry Development (2025). Belém’s Climate Paradox: Road for COP30 Pierces Through the Heart of Amazon - CVFV20.org. [online] CVFV20.org. Available at: https://cvfv20.org/belems-climate-paradox-road-for-cop30-pierces-through-the-heart-of-amazon/ [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

ORF.at (2025). Brasilien chartert Kreuzfahrtschiffe als Hotels für COP30. [online] news.ORF.at. Available at: https://orf.at/stories/3399898/ [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Cop30.br. (2025). Note on the report about construction works on Avenida Liberdade in Belém. [online] Available at: https://cop30.br/en/news-about-cop30/note-on-the-report-about-construction-works-on-avenida-liberdade-in-belem [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Bragazzi, N. and Garbarino, S. (2024). Understanding and Combating Misinformation: An Evolutionary Perspective (Preprint). JMIR Infodemiology. [online] doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/65521.

X (formerly Twitter). Stefan Homburg (2025). Available at: https://x.com/SHomburg [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

AR Göhring (2025). Antarktis-Eis und Arktis-Meereis wachsen wieder - von Fritz Vahrenholt - EIKE - Europäisches Institut für Klima & Energie. [online] EIKE - Europäisches Institut für Klima & Energie. Available at: https://eike-klima-energie.eu/2025/05/15/antarktis-eis-und-arktis-meereis-wachsen-wieder-von-fritz-vahrenholt/ [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Harambam, J. and Aupers, S. (2019). From the unbelievable to the undeniable: Epistemological pluralism, or how conspiracy theorists legitimate their extraordinary truth claims. European Journal of Cultural Studies, [online] 24(4), pp.990–1008. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549419886045.

X (formerly Twitter). Die diesjährige Schreckensmeldung der bezahlten Klima-Lügenwissenschaft lautete:... (2025). Available at: https://x.com/holger_wuttke/status/1924153133611053394 [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Jaroslav Myslivec (2024). It is all a conspiracy: Conspiracy theories about the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine. Ceskoslovenska psychologie, [online] 68(2), pp.111–134. doi:https://doi.org/10.51561/cspsych.68.2.111.

Daytonastate.edu. (2025). DSC Library: Finding Reliable Information: Bias, Preconceptions, and Logical Fallacies. [online] Available at: https://library.daytonastate.edu/reliable/logicalfallacies [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Rantanen, O. (2025). Sofia Virran reissusta repesi raivo. [online] Ilta-Sanomat. Available at: https://www.is.fi/politiikka/art-2000011395473.html [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

The importance of the messenger in climate change communication to farmers. (2025). Italian Journal of Animal Science. [online] doi:https://doi.org/10.1080//1828051X.2025.2515264.

THE POWER OF. (n.d.). Available at: https://fleishmanhillard.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/FleishmanHillard-Authenticity-Gap-Report-2021.pdf [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Cop30.br. (2025). Note on the report about construction works on Avenida Liberdade in Belém. [online] Available at: https://cop30.br/en/news-about-cop30/note-on-the-report-about-construction-works-on-avenida-liberdade-in-belem [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Unfccc.int. (2025). Available at: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Hey, E. (n.d.). United Nations - Office of Legal Affairs. [online] legal.un.org. Available at: https://legal.un.org/avl/pdf/ls/Hey_outline%20EL.pdf.

ECHR (2025). HUDOC - European Court of Human Rights. [online] Coe.int. Available at: https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22itemid%22:[%22001-233206%22]} [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Admin.ch. (2021). Available at: https://www.news.admin.ch/en/nsb?id=85865 [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Session 1b: Authorization of ITMOs. (n.d.). Available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/eng_Day02_Session%201b_Authorization%20of%20ITMOs%20%281%29.pdf.

US EPA. (2021). Electric Vehicle Myths | US EPA. [online] Available at: https://www.epa.gov/greenvehicles/electric-vehicle-myths [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Beyond doomism and solutionism in response to climate change. (n.d.). Available at: Beyond doomism and solutionism in response to climate change [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

Ipcc.ch. (2019). IPCC Chair’s Statement at YOUNGO’s Unite Behind the Science event. — IPCC. [online] Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/2021/04/23/ipcc-chairs-statement-unite-behind-science/ [Accessed 3 Nov. 2025].

US EPA. (2021). Electric Vehicle Myths | US EPA. [online] [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

Consilium. (2022). How is EU electricity produced and sold? [online]

Briefing on spatial requirements for a sustainable energy transition in Europe LAND FOR RENEWABLES. (July, 2024).

AXA.com. (2024). ‘The cost of inaction is far higher than the cost of adaptation to climate change’. [online] [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

Iom.int. (2020). In Central America, disasters and climate change are defining | Environmental Migration Portal. [online] [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

Jordan, M. (2023). They Fled Climate Chaos. Asylum Law Made Decades Ago Might Not Help. The New York Times. [online] [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

The concept of ‘climate refugee’: Towards a possible definition. European Parliament Briefing. European Union, 2023.

International Chamber of Commerce (2024). New report: extreme weather events cost economy $2 trillion over the last decade - ICC - International Chamber of Commerce. [online] ICC - International Chamber of Commerce. [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

Tan, S., Minifie, J., Jones, E.R., Daniel, C. and Bharadwaj, A. (2025). Economic Growth Opportunities in a Greening World. [online] BCG Global. [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

Green Jobs: Towards Decent Work in a Sustainable, Low-Carbon World, UNEP/ILO/IOE/ITUC, September 2008

Aryanpur, V., Balyk, O., Glynn, J., Gaur, A., McGuire, J. and Daly, H. (2024). Implications of accelerated and delayed climate action for Ireland’s energy transition under carbon budgets. npj Climate Action, [online]

Reuters (2025). Brazil state hosting COP30 denies new road linked to climate summit. [online] Reuters. [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

Poynting, M. (2025). What is the COP30 climate meeting, and where and when is it taking place? [online] Bbc.com. [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

Paraguassu, L. (2025). Deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon hits 11-year low ahead of COP30. [online] Reuters. [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

Brito, R. and Paraguassu, L. (2025). Brazil’s Senate approves bill to loosen environmental licensing. [online] Reuters. [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

Tamsut, F. (2025). Brazil approves oil drilling near mouth of Amazon River. [online] dw.com. [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

Hey, E. (n.d.). United Nations - Office of Legal Affairs. [online] legal.un.org. Available at: THE PRINCIPLE OF COMMON BUT DIFFERENTIATED RESPONSIBILITIES.

Ccegrp.com. (2024). The Carbon Market Divergence Has Begun. [online] [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

Regional Climate Week: Session 1b: Authorization of ITMOs. (October 2023).

Ipcc.ch. (2023). Summary for Policymakers. [online] [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

Hill Dickinson. (2025). A view of COP30: Tipping points, legal shifts, and the path forward. [online] [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

Global Tipping Points. (2025). Global Tipping Points | understanding risks & their potential impact. [online] [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

Ipcc.ch. (2017). Global Warming of 1.5 oC. [online] [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

Climate Action, European Union. (2023). European Climate Law. [online] [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

Süddeutsche Zeitung (2010). [online] Süddeutsche.de. Available at: “Wir brauchen keine Klimaforscher” [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

Żuk, P., & Żuk, P. (2024). Ecology for the rich? Class aspects of the green transition and the threat of right-wing populism as a reaction to its costs in Poland. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2024.2351231